It might seem like an incidental detail, but the fact that both of Jodie Whittaker’s season finales as the Doctor feature crucifixes—one that grants the demonic Tzim-Sha the powers of a god, the other a pilot’s seat for an evangelical Cyberman—offers a revelation about the era’s single most unifying theme: faith. This is a Doctor who has twice attended funerals, twice prayed to the universe, and as of this month’s season finale, twice faced religious extremists. But this avoids any chance of a crass Faith vs. Science battle by pitting them against the series’ first and most spiritual Doctor.

[Spoilers for series 11 and 12 of Doctor Who]

At the exact midpoint of her first season, Jodie Whittaker’s Doctor asks to join a prayer. Having lost a pilot named Eve in her plan to save a hospital ship, the Doctor spends the final scene of “The Tsuranga Conundrum” reciting a funerary incantation that mingles scientific exploration with religious reverence: “May the saints of all the stars and constellations bring you hope as they guide you out of the dark and into the light, on this voyage and the next, and all the journeys still to come. For now and evermore.” For this Doctor, traveling through time and space is an almost religious experience.

Among her litany of firsts, no other Doctor professes a faith. As India faces Partition in “Demons of the Punjab”, the Doctor officiates an interfaith wedding ceremony between Prem, a Hindu man fated to die, and Umbreen, a Muslim woman who’s the grandmother of her companion Yaz. “I know there aren’t many certainties in any of our lives,” says the Doctor, “but what I see in you is the certainty you have in each other. Something I believe in my faith: Love, in all its forms, is the most powerful weapon we have, because love is a form of hope, and like hope, love abides… in the face of everything. […] Which makes you, right now, the two strongest people on this planet. Maybe in this universe.”

That the Doctor believes in love and hope might sound trite. To some extent, it could be read as a metatextual metaphor for an era that desperately wants to say and believe in something, but hasn’t decided on what, exactly. But the Doctor’s speech is more nuanced than this. Whereas previous Doctors like Peter Capaldi’s have struggled with the absence of hope, or have suggested the balance between good and evil is a matter for scientific “analysis,” this Doctor frames her faith as a power between people—a hope that spans time and extends beyond space. Which is hardly flowery language for this flower-wearing officiant: having brought Yaz thousands of miles and 70 years from home, she already knows how small loves can travel through time.

But it’s the critically unloved 2018 finale, “The Battle of Ranskoor av Kolos”, which tugs at the season’s threads of faith and uncertainty like a doorknob tied to a loose tooth. Having escaped the Doctor in Whittaker’s first episode, the warrior Tzim-Sha fails upwards from fallen leader to false god. The story hinges on his teleport arriving in front of the Ux, two “faith-driven dimensional engineers” with the power to summon up sacred shrines and a spaceship whose interior looks suspiciously like a Welsh factory. The Ux’s unforgettably named planet Ranskoor av Kolos means “Disintegrator of the Soul,” and its psychically poisoned atmosphere warps perceptions of reality. Which might explain why the Ux, whose entire faith is based on doubt, spend 3,407 years immediately worshipping a blue-faced demon who wears trophy teeth like foundation.

By the time the Doctor and friends arrive, the Ux have been strapping themselves into Tzim-Sha’s electric crucifix, built to harness their power and destroy whole planets. This image of deceived devotees putting themselves through agony in order to commit genocide is emotionally charged, if thematically incomprehensible. But while the Doctor convinces the Ux their belief has been weaponized—”He made you destroyers. That’s no god!”—crucially, she never attacks their faith itself. Even as they turn Tzim-Sha’s crucifix against him, the Ux praise “the true Creator,” and the Doctor compares her TARDIS to Tzim-Sha’s shrine. “You’re not the only ones who can conjure stuff out of nothing,” she says as the TARDIS materializes. And in the episode’s climax, the Doctor squeezes her eyes shut, then looks up—and prays. “Might work. Please work. Universe, provide for me. I’m working really hard to keep you together right now.”

“Ranskoor” is far from a perfect treatment of religion. But ending the episode, and by extension the season, with the Doctor advising “keep your faith” is a striking change. In 1971’s “The Dæmons”, the Third Doctor had insisted that witchcraft, the supernatural, and all “the magical traditions are just remnants of [the alien Dæmons’] advanced science.” And it’s in 1977’s “The Face of Evil”, with the Fourth Doctor accidentally worshipped thanks to a computer-turned-god named Xoanon, when he gives his famous speech against organized religion: “You know, the very powerful and the very stupid have one thing in common. They don’t alter their views to fit the facts. They alter the facts to fit their views. Which can be uncomfortable, if you happen to be one of the facts that needs altering.” So in a show where ghosts and gods alike invariably turn out to have some perfectly rational explanation, this reinterpretation of the Thirteenth Doctor’s worldview to make the supernatural and the scientific two halves of the same hope, rather than dogmatically incompatible, has been an absolutely divine intervention from showrunner Chris Chibnall.

His prior work suggests religious themes abide with him. As showrunner of the Doctor Who spin-off series Torchwood, Chibnall scripted episodes about an enormous demon with a deadly shadow and a sex gas that, as the name suggests, kills people engaging in casual sex. That romantic relationships in general are arguably less common in his work might suggest why the Thirteenth Doctor has not had one, unlike her predecessors since 1996. And in Chibnall’s hit murder mystery Broadchurch, the Reverend Paul Coates as played by Arthur Darvill received notable praise for an unusually sympathetic portrayal of a small-town clergyman. This is not to speculate on whether the culturally Christian themes in his writing are or aren’t reflective of Chibnall’s personal beliefs. But these themes undoubtedly reflect the small-c conservatism in his Doctor Who, which belies the accusations of far-left “wokeness” against an era that has featured the Doctor rescuing a large corporation and unmasking the Master’s race to the Nazis.

Having tested the Doctor’s faith, her second season puts her through hell. Her oldest enemy breaks her hope. Her home planet burns. And the Doctor’s concurrent portrayal as a scientist takes the wheel, steering the show away from Rosa Parks and King James I, and towards Nikola Tesla and Mary Shelley. Religious imagery became less common, though by no means absent. In “Fugitive of the Judoon”, the Doctor and Ruth—soon revealed as another, secret incarnation of the Doctor—find sanctuary in Gloucester Cathedral, warning invading space cops, “This is a place of worship. Show some respect.” Before long, Ruth follows a mysterious message, “Break the glass, follow the light,” and rediscovers her identity as the Doctor, bathed in a golden light that evokes both the Baptism and Transfiguration of Jesus.

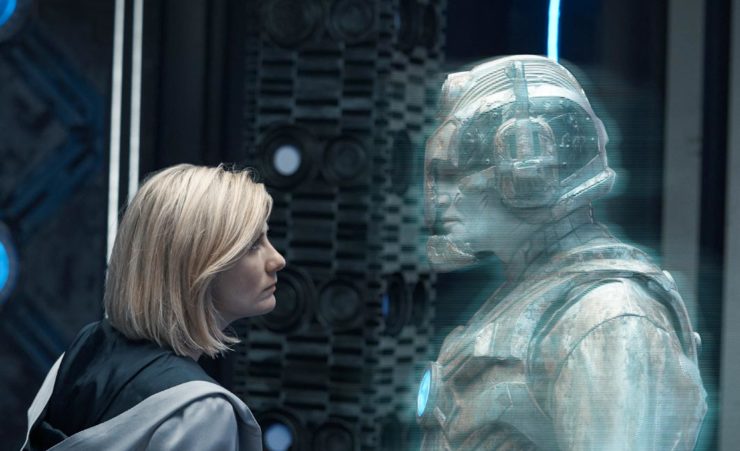

But the Thirteenth Doctor’s real moment of apostasy is her first encounter with “the lone Cyberman” in “The Haunting of Villa Diodati”, where Mary Shelley quotes her future husband’s description of the mysterious figure. “Dark. Charred by fire. Suspended over the water like a death god rising from Hades.” Perhaps more sinister than another false god, the Cyberman, Ashad, is revealed to have been “a willing recruit” who brutally murdered his own children when they resisted the Cybermen. He was, quite literally, eager to die for the cause, even though his conversion has gone wrong: “In death we are transformed, improved, updated, as you will learn.” And the Doctor, a woman who has described hope as her faith, loses—to a half-finished cyborg who describes his race as inevitable, a half-broken man who cannot be deconverted. Even his ship is steered with a skewed saltire crucifix. Though it’s odd that a religious Cyberman has less interest in “converting” humans than usual, in “Ascension of the Cybermen” he describes his holy mission like a crusade: “That which is dead can live again . . . in the hands of a believer.” And later, “As I began my blessed ascension, I was denied. At first I cursed myself, hid in the shadows, ashamed. But now I understand I was not discarded. I was chosen to revive the glory of the Cyber race. […] Everything is in me for the ascension of the Cybermen, and beyond.”

There’s a reason why fanatical extremists have been ideal foils for Jodie Whittaker’s most devout of Doctors, and it’s not simply that the character and her travels have been recast in a religious light. More than ever before, she’s built on a sense of hope. And so she’s forced to face pious certainty in the inevitability of despair. Where previous eras might come off as sanctimonious when setting skeptical Doctors against zealots, Chibnall and Whittaker made it a battle between two conflicting belief systems – a hopeful Doctor praying to, and pitted against, a universe that almost seems determined to break her faith.

Perhaps the most baffling critique of Whittaker is that her performance offers nothing new in the increasingly long line of Doctors. David Tennant had a big grin too. Matt Smith already squeezed every ounce of “childlike” from the character. And it’s true that Whittaker has walked back the tonal two-step of Peter Capaldi. But it’s been surprisingly rare to see any Doctor who’s so in love with the universe. Whereas previous Doctors traveled through time out of necessity, despite disillusionment, or to show off to their companions, Whittaker seems to be the first Doctor who travels utterly joyfully, for the sheer fun of it. She’s not running away from things—she’s running to them, uniquely positioned to see how love and hope abide like faith, through all her journeys still to come.

Max Kashevsky is a PhD candidate in political theory at the University of Cambridge. He’s also written the short story “Doctor Who: Short Trips – Still Life” for Big Finish Productions. You can follow him on Twitter @MaxCCurtis.